Undiscovered Particles

by James Romberger

from the Jack Kirby Quarterly #15, 2008

A young mind is blown, from Forever People #2

The Fourth World is Jack Kirby�s grand concept, the project in which he invested the prime of his skills as well as his highest hopes and ambitions. Kirby�s saga debuted in 1970. He hit the ground running; within a few issues his writing became more confident and he began to draw with unmatched clarity, grace and power, brought into focus by Mike Royer�s exemplary inking. Kirby put forth a very thoughtful and humane writing that helped form many of his reader�s views of the world. In this way he transcended the entertainment realm of comics to create something much more meaningful. He filtered his own experiences with violence into a philosophy that extended across his epic, from Orion�s attempts to overcome his aggressive nature and the examination of the principles of conscientious objection in �The Glory Boat,� to Mr. Miracle and Big Barda�s rejection of their military programming. In Kirby�s comics pathos is contrasted with irony to create relief, a classical formula he used effectively. The best stories of the 4th World read as literature.

For a variety of reasons, the 4th World was cancelled by DC before the end of 1972. The loss of his developing masterpiece as he was just reaching a career peak of performance hit Kirby like a hammer blow, according to those close to him. He went on to create other significant works, but rarely again touched the glorious synthesis of story and art seen in the best of the New Gods. DC owns the characters and concepts and uses them in combination with their other corporate properties. In 1982 DC�s Jenette Kahn and Paul Levitz offered Kirby creator credit and a percentage of royalties for the Fourth World for redesigning it for use in the Super Powers TV cartoons and toys, a gesture that meant a good deal to Kirby and his wife Roz. DC also offered him twenty-three pages to write and draw a conclusion to his story in the final issue of reprints of his original New Gods comics. Within the limitations he was given, Kirby produced one of his last great stories, �On the Road to Armagetto�. Unfortunately, it was rejected by DC. Kirby amended the story, and it was inked and lettered by Mike Royer. Its pages were later distributed in altered form throughout Kirby�s 1985 graphic novel, Hunger Dogs. Sadly, with DC�s recent reprinting of Hunger Dogs in their 4th World Omnibus Volume 4, that story remains unavailable to be read as he intended.

____________________________________________________________________

For his conclusion, Kirby chose to focus on something meaningful that was possible to bring to succinct resolution. One of the most significant themes present in Kirby�s complex, interwoven plotting in the 4th World is that he absorbed the aspirations of the psychedelic movement, and recast it in his own image. In 1970 Kirby was aware that a key demographic for his work was the college-age kids that had embraced his Marvel work. He created characters for DC that were geared to and reflected that market. The first of Kirby�s new comics completed on his board was The Forever People #1. The dreams of the flower children had been occluded by Charlie Manson and Altamont the year before but you couldn�t tell from the optimism Kirby invested in his super-freaks.

The Forever People is about a small unit of young New Gods who join their planet�s war, but deal with crises using technology, compassion and their individual skills. The Forever People as superheroes are an idealized version of what hippies should be: calm, gentle and intelligent. In cases where they are unable to cope, they join to form the Infinity Man, an entity of indeterminate power and personality, however, this device was diminished as Kirby progressed. Simultaneously, Kirby took over a staid DC title, Superman�s pal, Jimmy Olsen. Square Jimmy suddenly seemed truly young, hurtling at breakneck speed into Kirby�s ominous interzone of psycho-cosmic warfare. Kirby came up with many inventive ideas from the world around him, distilled from current events, hit films, and scientific magazines. He explored the then-nascent science of genetics with his �DNA Project,� a U.S. Government operation that could endlessly generate the types of imaginative Jimmy mutations the title was notorious for, and also created �The Hairies,� a commune of technologically advanced �DNAlien� clone hippies who travel a tunnel complex called the �Zoomway,� in a dragon-decorated missile carrier known as �The Mountain of Judgment.�

The Hairies' Mountain of Judgement, 1970

Kirby�s hippie characters may have been inspired by the real-life pioneering exponents of psychedelia, the Merry Pranksters. This may be supported by the fact that the Pranksters were, like the Hairies, the result of a Government experiment. Prankster founders Ken Kesey (author of One Flew Over The Cuckoo�s Nest), Ken Babbs, and Stewart Brand (later editor of the Whole Earth Catalog) all attended Stamford University in the late 1950s and there participated in tests of LSD by MK-ULTRA, a long-running mind-control program overseen by scientists under the wing of the CIA. Kesey and his fellow subjects were so impressed by their experiences on acid that they became advocate distributors of the drug and facilitated the rapid spread of psychedelic culture. They believed that LSD could change the world. They threw the earliest public Acid Test parties in San Francisco in collaboration with the Grateful Dead. The Pranksters� acid-proselytizing tour of America on their psychedelic bus �Further� was reported by Tom Wolfe in stream-of-consciousness style in his famed 1968 book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

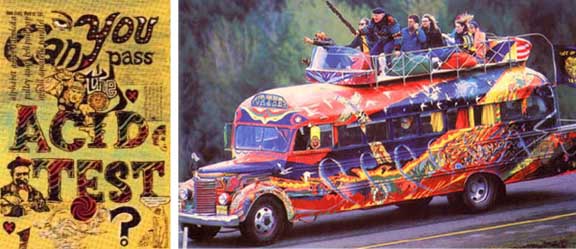

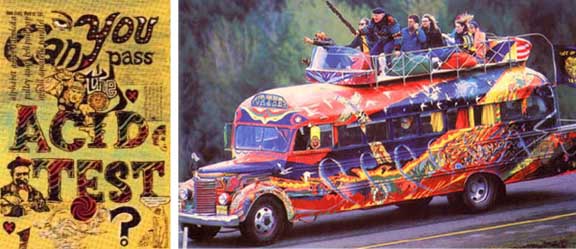

Kirby's Thor on Acid Test flyer, and the Merry Prankster's bus Further, 1966

Kirby�s work figures into the Prankster�s saga: Wolfe writes that Kesey is frequently consumed in reading Marvel Comics, and a Kirby drawing of Thor is prominent in a Prankster poster for an 1965 Acid Test. Kirby is one of the most important psychedelic artists of that era. It has rarely been suggested that Kirby took LSD himself, but his combinations of solid spatial and figurative composition with abstract technorganic design in the eidetic pageantry of comics like Thor bear up under scrutiny magnificently whilst tripping. Kirby�s assistant at the time, Steve Sherman, laughingly said that Jack�s young staff �gave him lots of pot� (The Jack Kirby Collector #6). When interviewed, Kirby cautioned about drug experimentation: �I believe that any sort of stimulant or irritant used for any sort of motivation...it�s kind of a wild thing without guidelines...I won�t hang anyone up on a gallows who uses drugs, but I won�t respect them, either� (TJKC #42). For his family-friendly DC comics, Kirby�s cosmic consciousness catalyst is not LSD but the Mother Box, a technological link to �the ultimate mystery, The Source� that must be built, and its wisdom earned, by its bearer. Mind-expanding effects are also exhibited by Forever People member Serafin�s Cosmic Cartridges, all of which have properties relating to �all there is.�

The Forever People�s driver is Big Bear, who resembles aspects of both Kesey and Neal Cassady, the Beat legend who joined the Pranksters as navigator. Another key Prankster figure, Cassady�s friend Carolyn Adams, known as �Mountain Girl,� has a 4th World equivalent in the Daisy May-outfitted Beautiful Dreamer. The magic bus �Further� can be seen reflected in The Mountain of Judgment of the nomadic Hairies. Jimmy Olsen witnesses several manifestations of the Acid Test music-lightshow multimedia events in the Hairies� dance concerts and projections, one of which (Jimmy Olsen #134, p.12) incorporates a Kirby collage cut from photos of Jimi Hendrix that appeared in Life magazine (issue dated 10/03/1969). The Hairies are allied with the motorcycle gang the Outsiders, who might have reflected the Prankster�s brief involvement with the Hell�s Angels, but were also acknowledged by Jack as referencing the bikers who frequently ripped up the canyon below the Kirbys� California home. In the end, Kirby�s characters are melds of many different sources, and even if Kesey�s crew were not a direct inspiration, Kirby�s origin for the Hairies mirrors the Pranksters� covert genesis.

Kirby�s original series deliberately left many of the boundaries between his heroes and villains ambiguous. The Pact that secured the truce between Apokolips and New Genesis that would be broken by Scott Free and precipitate the events in Kirby�s storyline is itself a cold business: Highfather traded sons with Darkseid. Family values are strangely inversed in the 4th World. All along, Darkseid seems very concerned with the fate of his son, Orion, but strangely, Highfather seems disinterested in the concerns of his progeny, Scott Free aka Mister Miracle, who is raised in the hellish orphanage on Apokolips. The youngest of the New Gods is Esak; he appears to be at most nine years old. He does not seem to have parents, and is allowed to roam space and time as apprentice to the amoral scientist Metron in New Gods #4. In one of his other few appearances in the original comics in FP #7, Esak must beseech Highfather to save the Forever People; it is one of Jack�s gentlest scenes.

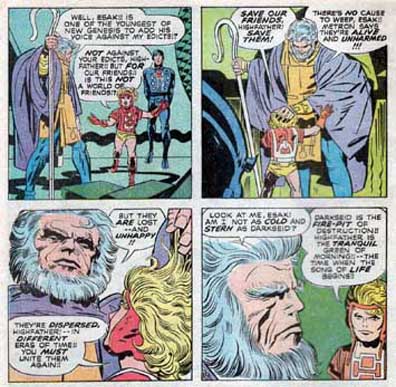

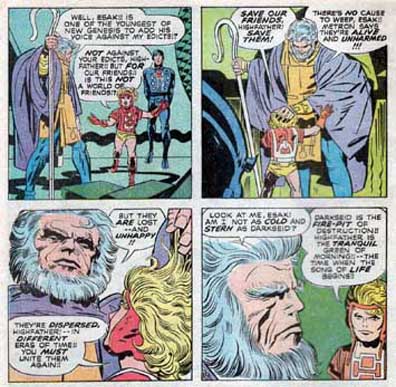

The clear view of Esak, from Forever People #7

But, Darkseid allows the Forever People to escape repeatedly, saying, �Greatness does not come from killing the young� (FP #8). When the hammer came, Kirby exiled the Forever People to a distant, verdant world and left the seemingly inevitable final battle between Darkseid and Orion hanging. Shorn of Jack�s fire, Mister Miracle limped to his belated wedding with Big Barda, presided over by a noncommittal Highfather. There was no acknowledgement of unresolved traumas such as Scott Free�s sacrifice for the sake of peace. Kirby was already elsewhere.

_____________________________________________________________________

When in 1983 Jack was asked by DC to complete his saga in one chapter, he looked at what he had done more than a decade before and, out of all possibilities, chose the theme of the betrayal of ideals to close out his saga. The overriding theme that he saw in the New Gods tapestry is that he had hoped and believed that the young could and would tackle the evils of their day with ingenuity and compassion. As the promise of the sixties faded, these aspirations were not borne out. He watched expanded consciousness give way to drug addiction, sexual and racial equality slow in coming, wars beget more wars, the environment steadily worsen because of individual and corporate greed and exponential population growth. America was sliding through the Reagan Years. Jack�s initial, thoughtful response was a short allegory that left the mystery of his unfinished epic intact, but that condemned, with little equivocation, the failure of the generation in whom he had invested his hope.

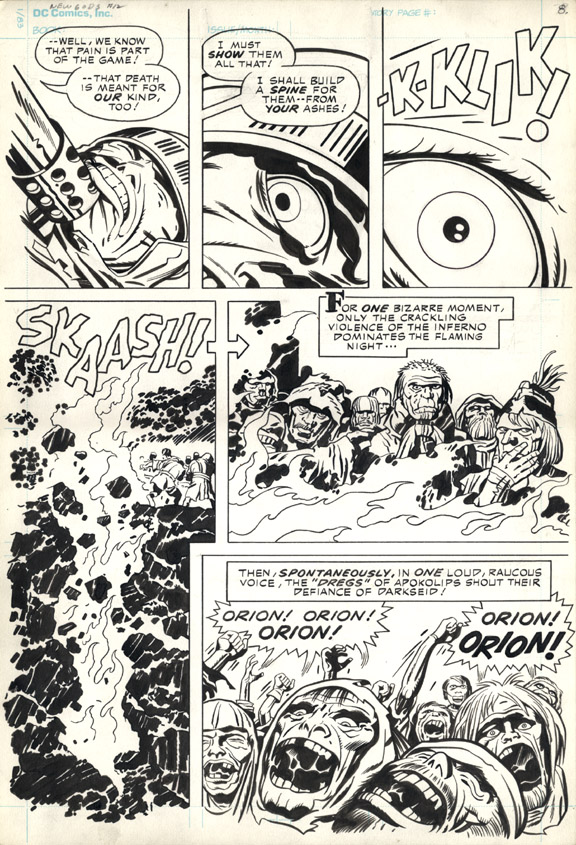

Kirby did some of his best late-period art for �On the Road to Armagetto.� By this time Jack no longer drew supple, idealized figures; his characters seem compressed, reflecting his own physical aging, but for all that his drawing is no less vigorous. Despite the cartooniness Jack was veering towards, due in part to his most recent animation design efforts, there is none of Kirby�s usual humor in this piece. It�s dead serious. Kirby�s blackspotting becomes abstract and patterned, and the open outside borders create a vignette effect, as if the entire story is a nightmare. And truly, as much is hidden as is revealed in this oddly cinematic fever dream. In Jack�s finale, the enraged Orion is only seen in flashes as he infiltrates Apokolips� capital Armagetto and incites the slum-dwelling Lowlies to revolution.

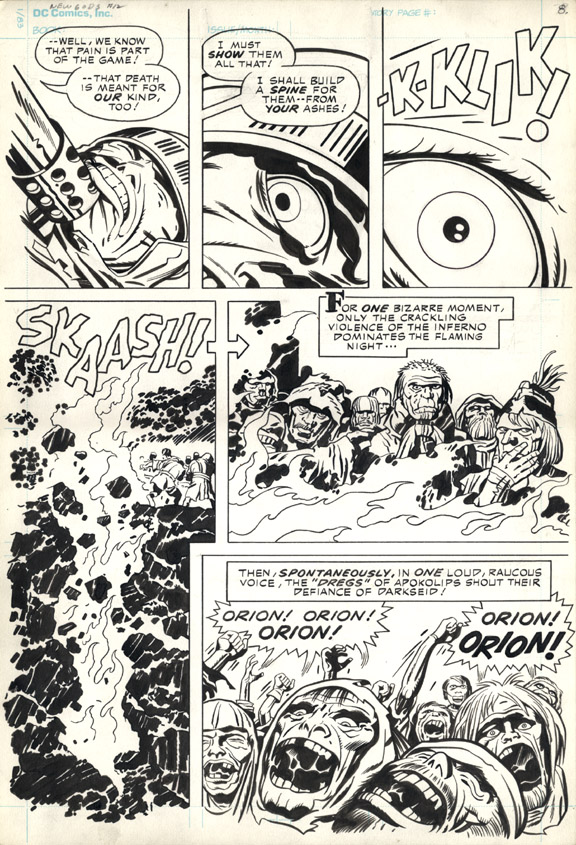

The Lowlies rise, from On the Road to Armagetto, 1982

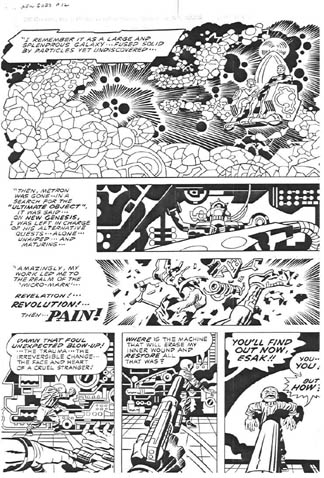

Darkseid�watches his WMD experiments, postures, mugs, and�spars with Himon.�An obviously significant but out-of-panel character responsible for Micro-Mark nano-bombs is revealed to be a horribly disfigured, swollen-headed Esak. Metron has deserted the child for years to study in solitude. After an accident mutilates the boy, he is thoroughly corrupted and goes over to work for Darkseid. As the mob approaches, Darkseid turns tail and escapes, leaving Esak to�face the killing machine Orion. Esak attempts to murder Orion�s posse, then testifies to his misfortunes.

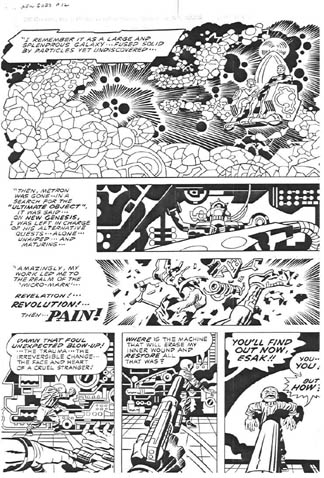

Esak's fall, from On the Road to Armagetto, 1982

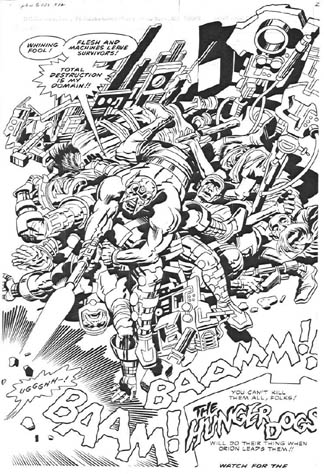

The story Kirby originally submitted ended with the splash on page 23�of Orion on top of a pile of corpses, shooting the off-image Esak. This is Jack�s �holocaust borne on flowers�, his answer to the �nature vs. nurture� questions he had brought up with his DNA Project and the Pact. Orion�s upbringing is completely negated by his Apokoliptic genetic baggage. The flower children do not save the world, perhaps because New Genesis doesn�t care about or keep track of its children. This was intended to be Jack�s final word, then: a fatalistic burst of ultraviolence more akin to Sam Peckinpah and the Druillet books that he admired.

No doubt Kirby felt it was his prerogative to finish his epic in his own way. Over a long career�he had�proved time and time again that his ideas and instincts were sound. His problems occurred when he was being second-guessed. Still, after DC rejected the story, a second denial of his New Gods, Kirby persevered. The �piece of the action for redesign� deal DC gave him was unprecedented, so he did what he could to satisfy their wishes. The�story mutated into an�intro to Hunger Dogs. He added two moving pages wherein Orion regains his senses and absolves Esak, mitigating the darkness somewhat. The �child, fallen upon cruel days� grew away from the Source, but is forgiven. Orion witnesses the Source do a cosmetic makeover of Esak�s ravaged husk, saying, �Judge him as he was, not as he became.�

On one level Kirby apparently came to grips with his disappointment with the Hippie generation, on another, with the interruption of his opus. On yet another level he is still defiant, in effect disclaiming to the reader all of the presumptions made on his characters by others, and perhaps even what was to follow in the adulterated Hunger Dogs. The final printed graphic novel has its own merits, but reflects much interference with Kirby�s creative process. �On the Road to Armagetto� is Jack Kirby�s dark codetta to the New Gods, an apotheosis of unending conflict.

© 2011 James Romberger, New Gods © 2011 DC Comics