Journal, March 22nd, 2002

Saturday we went to Robert Hawkins� show at Gracie Mansion Gallery. I like Robert. He told me he is living in the Barbican. I told him I had one of the best jobs of my life when I used to serve breakfast to 400 construction workers there, hungry men who were glad to see me. Walter Robinson was there and Rick Prol and I was listening to them talking about the Damian Hirst show. W was quizzing Rick as though he was trying to understand why he liked the 15 feet high paintings. In an exasperated way I said, �We got the fuck blown out of us and now we want everything big.� W asked if he could quote me on that and I have been regretting cursing ever since. When I looked around the room at Robert�s show my hypothesis seemed to be validated, he had a picture of a huge turkey on the wall over a giant two-headed hotdog, the most overblown American with a capital A imagery. On the opposite wall were an ark and a baby bear in a rocking cradle. He also had a painting of a flaming building. The selections he made, which I asked him about, were not totally conscious, except the burning building, but the psychology was screaming from the walls at me.

Franz Kline,"Study for Harleman," 1960

May 1st, 2002

The next show at GM Gallery was the packed David Sandlin show - I was shocked to see another painting depicting a burning building, the same size (roughly), hanging in the same spot. I asked Sur Rodney Sur if he had been aware of this when he was hanging the show. He seemed a little bewildered and said, �No.� Even when we are apparently functioning normally our psyche has been altered. The horrific genius of the terrorist act was that they left time for the media to respond, and created a loop that would replay over and over again in our minds, constantly opening the wounds by picking at the scabs, as it were. Nor can I be surprised to hear that other people are responding to very large-scale work, either. America�s post-war heyday was a celebration of strength and musculature, a mark- making lexicon that formed a vernacular of American visual language. It recognizes itself as other from Europe and embraces the influences of Jazz and Beat. It withdrew from drawing rooms and salons and punched itself free from the walls. It identified itself as American and not the bastard child of the Europeans. It worked big and tough and it did not give a damn about what �they say�, having plenty to say itself. After World War II it began the business of living. It had been over there, and come back to its homeland and loved her with all her rich textures and different colors. All appeared in lobby sized paintings made for skyscrapers, power symbols for the burgeoning new world, in this apex moment of American Art. The abstract expressionists Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko and those who painted with them all worked on a monumental scale. They were strong and defiant and they embraced all things American. It was the first movement outside of Europe to stand as by itself and again to some it will be a remarkable comfort and reaffirmation in the post-9/l1 era. But, they were not dealt a blow on home soil though we will reference their lexicon. We will now respond by standing up and embracing the big. All Americans know that bigger is better, even when the intellectual elite ascribe it gauche, forgetting itself for a moment to be immigrant sons. We are a culture which is not afraid of the new and will embrace and will make newer, better things, which cannot be knocked down. We, unlike our American predecessors, will use allegory and metaphor to deal with our grief and anger, that we might want to strike back in anger for what was done to us. The event of September 11th was vast and when one turned to look back into the billowing smoke from the twin towers we looked into the eye of God, for we felt our humanity stirring in us and recognized it in the flames, but knew the flame to be pure evil and gazed moth-like drawn to that dark side of our psyche to rage and retaliation. New Yorkers are tolerant people because of the nature of New York and so it is abhorrent to them for us to respond so venally. We will use our new American language and our old and we will use it big and loud and we will do better and bigger work and as they say, we will show them.

Jackson Pollock, drawing, 1949

Later

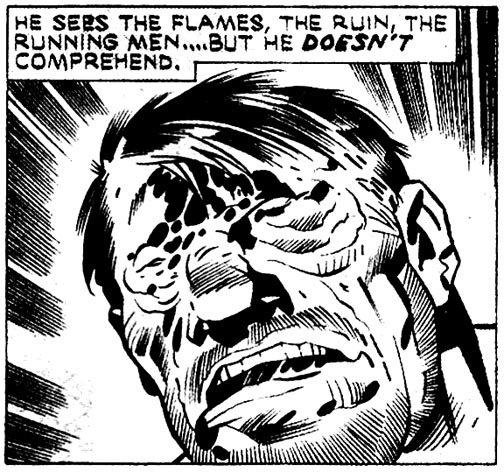

The comic world responded and was embraced by the press and public in a way I have never seen. Every week the New York Times Art section recommended a comics exhibit and there were full-page reviews of the various books and exhibitions of comic pages done around the topic of 9/11. I went to severa1 of these events, which were crowded with people who wanted to make some sense of the horror that had occurred here in New York. Many lingered for hours reading in minutiae the pages on the wall or staring at the glossy drawings of heroic firemen. They received no divine lightning bolts on those occasions but left nonetheless feeling better than when they got there. The content of the comics was not especially the significant thing; it was the American voices, written out in comic slang and the unquestionably homegrown nature of the medium, which salved our wounds. Comics create new familiar images with which we can subliminally fight to counter and supersede the criminal loops that had been planted in our minds. These American images of empowerment provide a potent tool to deploy against the post-traumatic stress from which we suffer. The outpouring of care from the comic artist community somehow reassured us that our collection was still safe under our collective bed, even if the big bad wolf had been sleeping in it. Whether or not the quality of the work was the finest became irrelevant to its creation. A community made its presence felt and although people could not tell why they responded so deeply to these shows and collections they felt like comfortable old gloves. Its heroes become the older sibling who always knows how to handle problems, in these worlds there is no uncertainty, emotions are telegraphed directly; happiness and sadness are clearly delineated. We are able to relate guiltlessly. Hero-based comic art responded and was built on the same frames of reference as any other American Art form by those who went through World War II: it reflects all the scale and posture of its returning forces. It is in the pages of comics where men and women, larger than life, battle it out for abstract ideals, and their feats relate to powerful gestures, with big swooping lines that deliver a punch. In the ann(u)als of comics we see the desire to assure that things will be bigger and better (classically speaking), and there will always be a next issue, the continuation of all things right.

Jack Kirby, "The Partisans", Our Fighting Forces #155, 1975

| Comic Art Forum | Ground Zero | 1xBet | Arteries |