Seven Miles a Second at PPOW,

Review from Art In America, June 1994, by Calvin Reid

This exhibition presented the original artwork from Seven Miles a Second, the comic-book-format autobiography that Wojnarowicz conceived with collaborator James Romberger. The work, which is still unpublished, is an adaptation of the autobiographical writings in Wojnarowicz's book Close to the Knives as well as some of his journal entries. Seven Miles A Second vividly details the story of his life as a teenage hustler on 42nd Street, his later battle with HIV infection and his stark confrontation with his own imminent death and the deaths of those he loved. The images are provided by Romberger, a ubiquitous figure within the Lower East Side demimonde of art, music and creative nonsense.

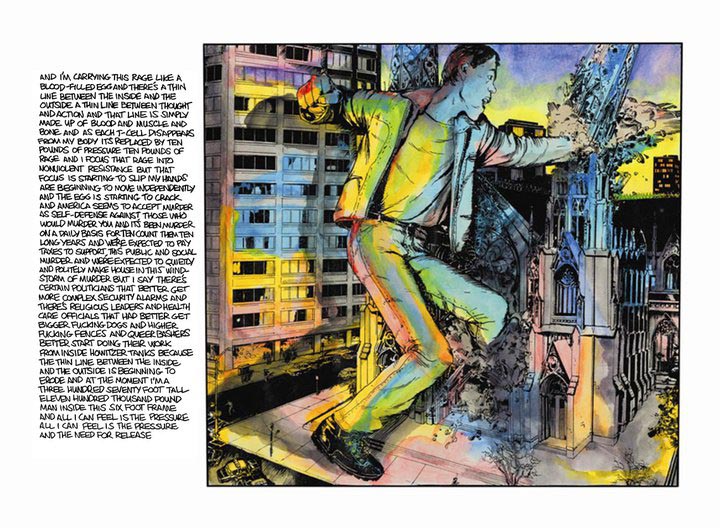

Divided into three sections ("Thirst," "Stray Dogs" and "Seven Miles a Second"), the work focuses on Wojnarowicz's early, hardscrabble life on the streets. It makes no mention of his later status as an artist, emphasizing instead his wildly hallucinatory inner life and his burgeoning rage. In stark, asymmetrical panel compositions, Romberger effectively translates Wojnarowicz's surreal visions from the written word to the drawn image. We see a grimy derelict dancing in the dazzling light of a cathedral; a ferocious stray dog gunned down on the subway tracks; a screaming man walking through open space high above the city streets; and a giant, vengeful Wojnarowicz shattering the towers of St. Patrick's Cathedral with a blow from his fist. Romberger renders Wojnarowicz's moments of delirium and violent frustration as well as interludes of tenderness and passionate attachment.

In one spectacular spread (which alludes to Wojnarowicz's own pictorial imagery), Romberger depicts Wojnarowicz, elongated limbs splayed out into space, atop a giant train hurtling across a vast wasteland. Produced over the course of several years (Romberger completed the work after Wojnarowicz died in 1992), the drawings show some variation in style. Romberger turns this inconsistency to advantage, though, using his expressive, roughly articulate line to convey the lurching emotion and turmoil of Wojnarowicz's life.

The comic-book artwork held up surprisingly well under the demands of gallery contemplation. The show illuminated the process of illustration, allowing us to examine the ragged, lively accumulation of visual incident on the surface of the heavily worked pages. And though never intended as part of the work's primary visual experience, the markings, corrective patchings, erasures and traces of opaque Whiteout enable us to follow the trail of Romberger's visual thought, revealing the editing and reshaping that go into such a revelatory work of art.